In the journey of a succulent enthusiast, learning propagation comes early. After all, it's the best way to get more plants. And, for the most part, our fat plant friends do an excellent job at propagating themselves.

But some plants are tough to propagate. It's already painful enough to pluck the leaves and ruin that beautiful symmetry - if you're not certain that leaf will successfully become another plant, the process can be daunting.

And so the use of rooting aids has arisen. But which one to use? Sublime Succulents is on a quest to find out.

Jump to:

Experimental Set-Up

The Plant:

A friend gave me an Echeveria he didn't want. It was a fairly large specimen, and in good health, but it was quite etiolated. Lacking proper sun stress it was difficult to tell what species it was, but I hazard a guess at Echeveria agavoides.

You can see an un-etiolated (but not sun-stressed) Echeveria agavoides on the left, and my specimen on the right. Regardless, as mine was healthy but etiolated, it was a prime candidate for disassembling for propagation.

Materials Used:

An Echeveria agavoides like this one from Leaf and Clay.

Some regular rooting hormone, easily purchasable online or at your local home improvement store.

I literally just used the honey that was in my cabinet. Honey is often touted as a miracle substance and used for all sorts of things. I don't often buy into that kinda stuff, but it is pretty great. The reason we use it for a rooting aid is that it has antiseptic and anti-fungal properties, which help to protect the propagations.

Anyway, make sure you have real, natural honey. We need those mysterious, magic parts of honey to make this work - not the sugar syrup from artificial honey.

Again, your standard over-the-counter cinnamon. We've all got it on our spice rack. It works for much the same reason as honey - it keeps bacteria and fungus away.

If that's the only criteria we could use hand-soap, right? I don't know, probably not. I didn't come up with this stuff, I'm just testing it.

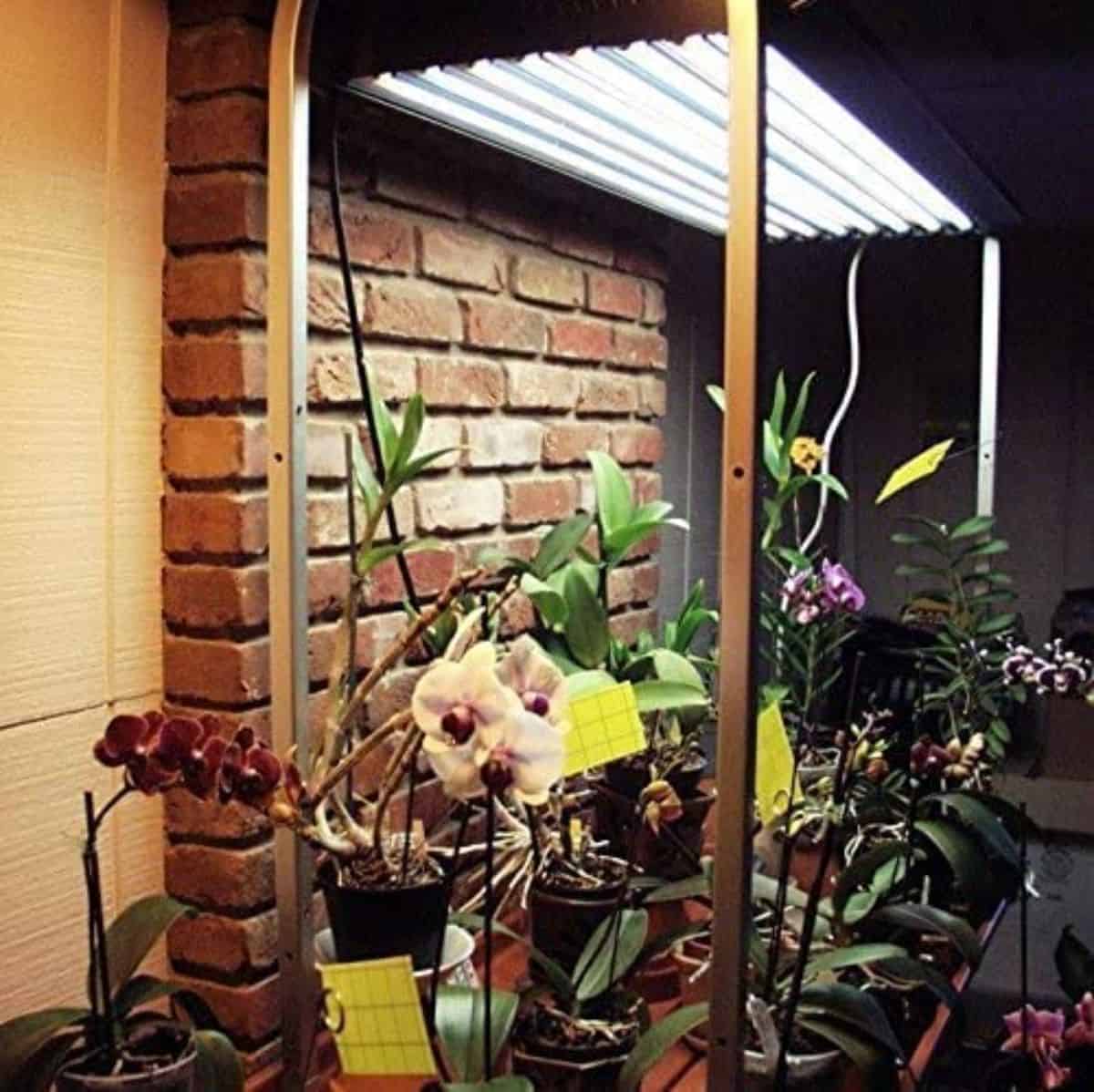

A grow light was used to standardize the light received. I used this one, in particular, a T5 full-spectrum tube light. Indirect sunlight works for propagating too. If you need help pick a grow light, check out this article.

Additional Materials:

- Some soil to place your propagations on. If you need help choosing a pre-made soil, look at our roundup of the best succulent soils. If you want to make your own, read this guide on everything you need to know about soil.

- A regular old spray bottle. I just used an empty cleaner-spray bottle that I had rinsed with vinegar and isopropyl alcohol to clean.

- A place to put your dirt. I used biodegradable planters, but it doesn't matter. Use a plate or some cardboard.

The Treatment Groups:

No products found.

Now, this experiment isn't so thorough that it's publish-worthy - there is far too little data. However, the results are noteworthy because it was tightly controlled.

When conducting an experiment, you only want to test one variable at a time. That way, you know nothing is influencing anything else. In this experiment, we wanted to test which rooting aid was most effective at encouraging successful propagation.

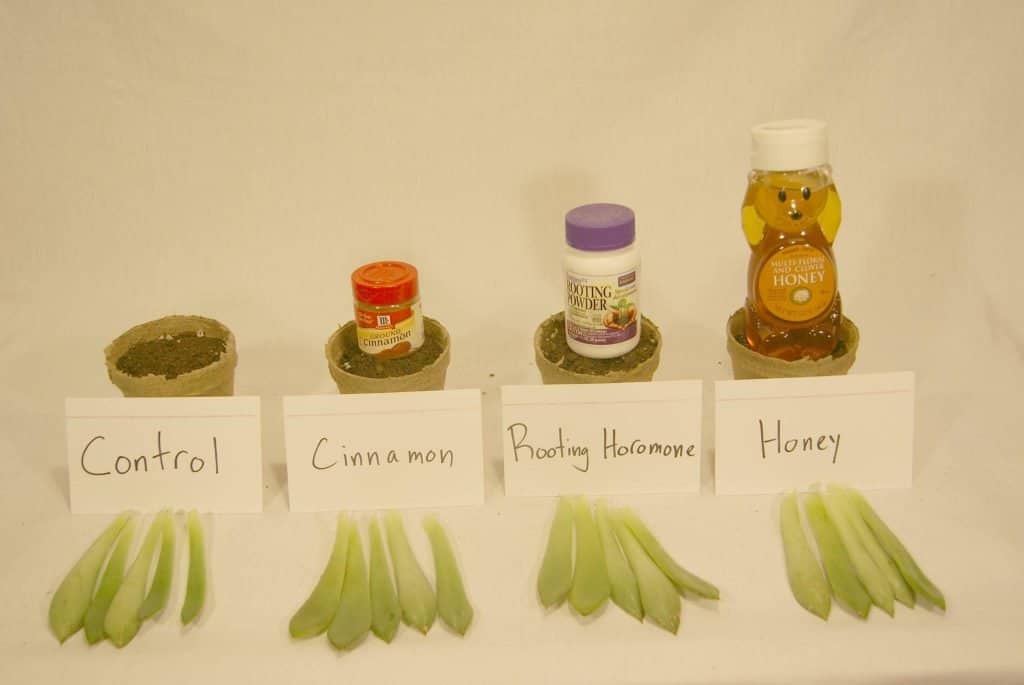

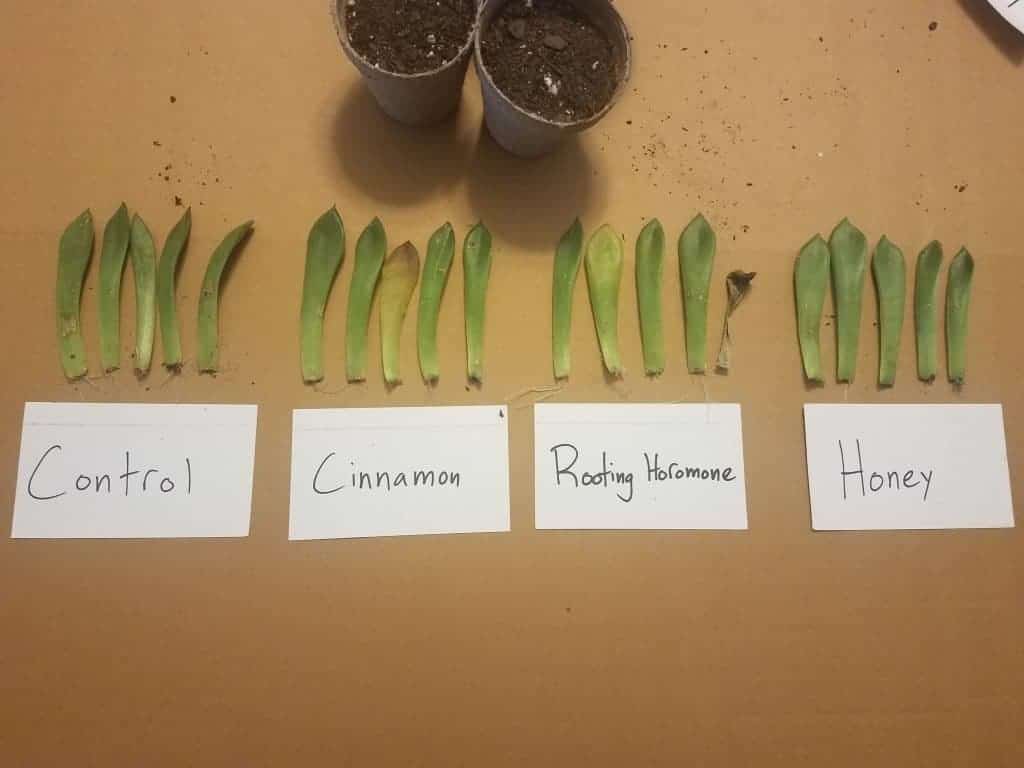

Our variable here was which rooting aid we were using. So we use a different one for each "treatment group". We're testing 3 rooting aids: honey, cinnamon, and rooting hormone. However, we have 4 groups. That fourth group is called the "control". The control is the baseline that we measure everything else to. It's an example of normal propagation without anything added.

I said this experiment was "tightly controlled". What that means is we've eliminated every possible variable other than the one we're testing. All the leaves came from the same plant, they were all under the same light, they all got misted at the same time. You see where I'm going with this? Everything is the exact same - except for the rooting aid. It makes sense, right? That way we can't attribute the difference to, say, some of the leaves coming from a different Echeveria.

Methods:

- All leaves were plucked from the mother plant at the same time using the proper technique. Leaves that weren't separated well were discarded.

- Leaves were divided into the 4 treatment groups (control, honey, cinnamon, rooting hormone) randomly.

- Treatment was applied immediately upon being sorted. It's important that rooting aids be applied before the callus forms. The callus is like a scab - it keeps things out. Rooting aids are much less effective if applied after the callus forms. Application is as simple as dipping the open "wound" of the leaf into whatever substance you're using.

- Four small, biodegradable planters were filled with soil. Each treatment's leaves shared a cup. Leaves were placed on top of the soil.

- A grow light was suspended above the leaves at a distance of two feet. It was hooked up to a timer set to be on 12 hours per day.

- All leaves were misted every 2 days with a spray bottle.

- Ran experiment for 54 days, then ended and collected data.

Experiment Results

The results were inconclusive.

You can see that there's been little progress - even after 54 days. Succulent propagations take a long time to reach maturity, it's true. However, they usually get started pretty fast. There's a dead leaf, and a couple that are on their way out. That's normal. Propagation is hardly a guaranteed thing.

Let's zoom in.

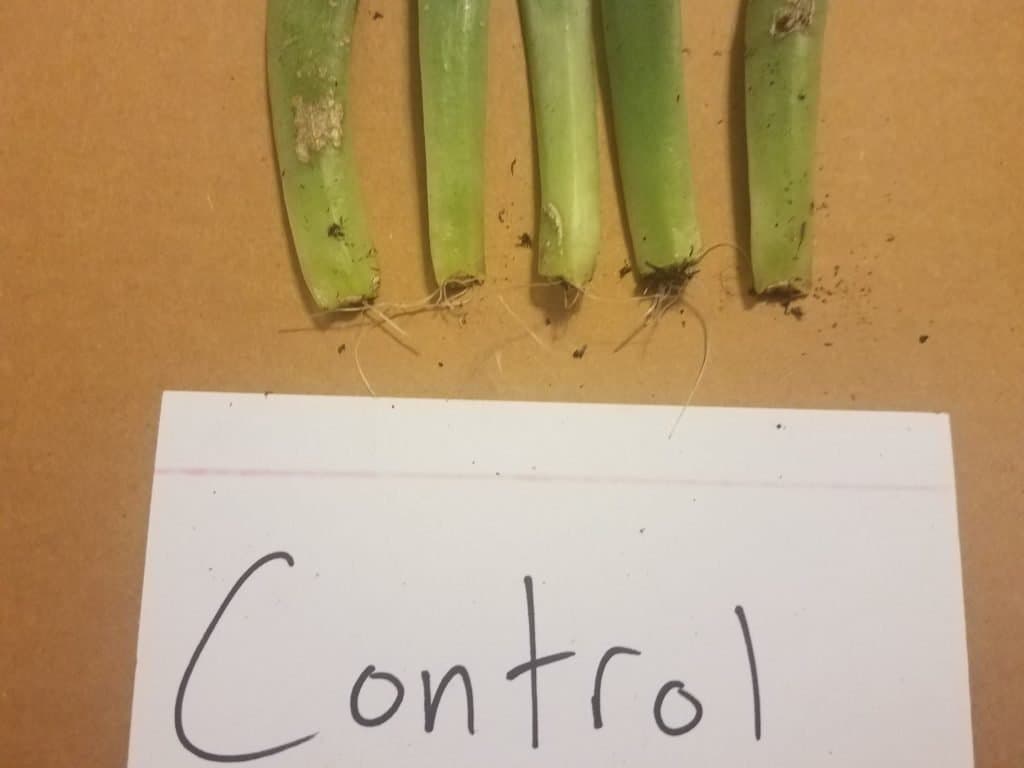

This is the control. It's our baseline because it is a natural propagation with no additives.

And it seems to be about what you would expect. ⅘ leaves have got some roots. Slow growth, but normal.

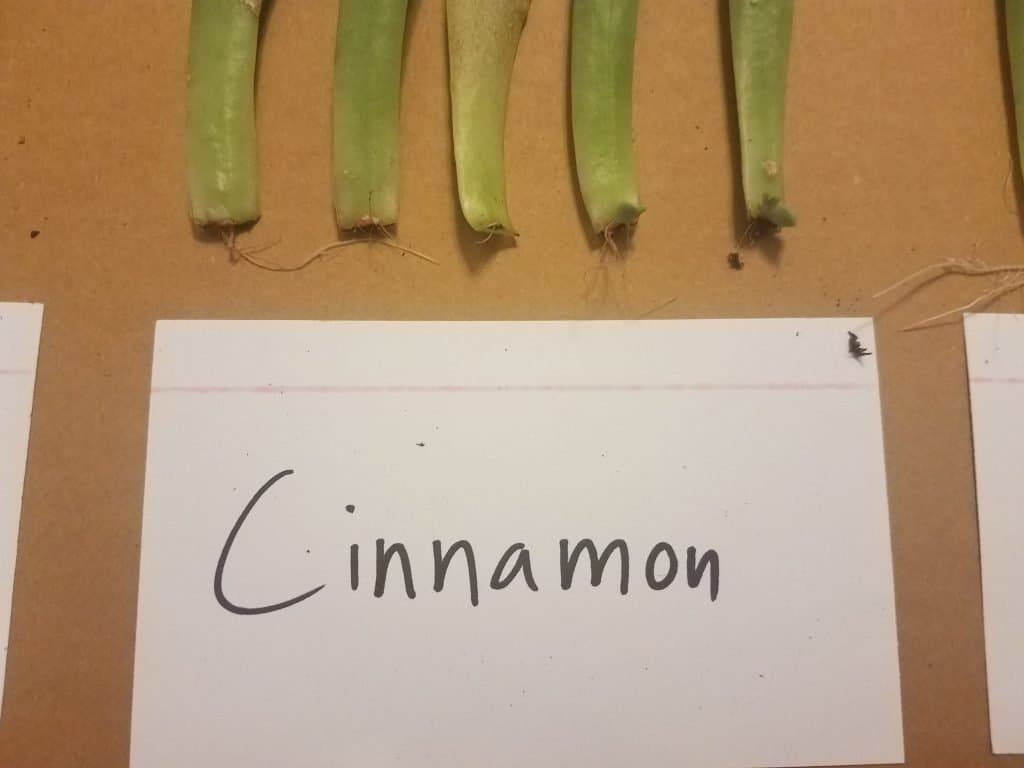

Let's check out cinnamon next.

This one is pretty interesting. You can see that there are fewer roots than in the control. However, this group has 2 small plantlets on the right two leaves. That's more important than roots, I'd say. Almost every leaf prop will grow roots, but not all of them manage to get leaves going.

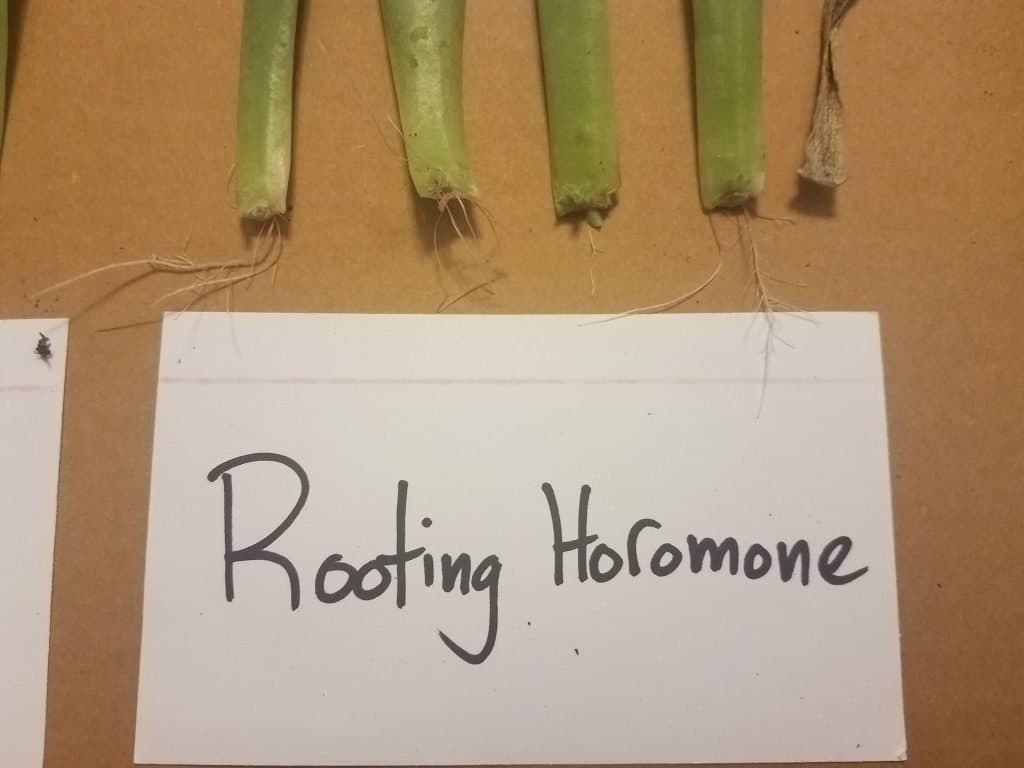

Next is the rooting hormone.

Right off the bat, it's easy to see that this group has significantly more developed roots than the other groups! It also has two small plantlets, but that last leaf is dead. One can only wonder if it would have been fruitful, had it not withered. Alas, cruel fate.

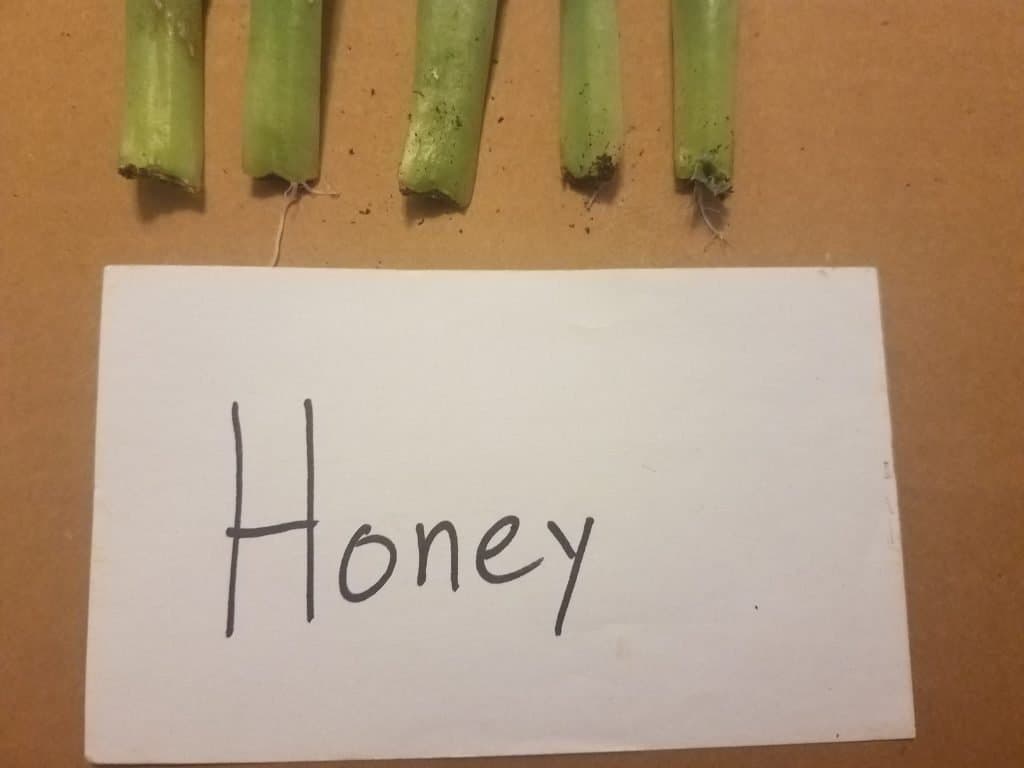

Last is honey.

Interesting. It has, by far, the least roots of any group. It does have the most developed plantlet though! I'm inclined to believe that is a fluke - that leaf was particularly plucky; the honey had little do with it. Of course, we can't really say for sure because we didn't test enough leaves.

Discussion

Unfortunately, the results were not so clear that we can immediately decide which substance best helps your propagations succeed. The results were a mixed bag.

It was pretty clear that rooting hormone powder promoted healthy, well-developed roots. Honey seemed to slow the process, actually. When compared to the control, the difference is stark. The jury is still out on cinnamon though!

To improve this experiment (and every experiment), we could have gathered more data. We'd need more plants than just one, though. That would loosen our control, so we'd need even more data to make up for the discrepancy. See where I'm going with this? That's why real research is expensive and time-consuming. However, these simple home experiments work great for informing our own opinion.

For some tasty irony, check this out:

What you see there is the mother plant, post-plucking.

I actually plucked more than the 20 leaves used in this experiment. I pulled about 30. The ones I decided didn't look as healthy, or I didn't get a clean break, I just threw back in the pot with their mom.

But look at that! Those plantlets are CLEARLY much better developed. It's hard to distinguish the roots from the other junk in the pot, but the ones you can see are really nice.

What does this mean? Is it better to propagate them with other plants? Do they prefer the same soil as their mother? Is natural sun better? Do they really thrive off neglect, growing just to spite me? Who knows, that's a whooole 'nother experiment.

Maybe we should just let nature do its thing, huh?

Bonus

I enjoyed this experiment so much (and you all did too!), that I decided to run it again with a different plant! It's currently in progress, but here's a sneak peek!

Rooting Aid FAQ:

Not everyone thinks about using rooting hormones or natural rooting aids to help their plant form strong, healthy roots. If you are new to the idea, you will find the following frequently asked questions section along with the answers very useful.

Q: Is Cinnamon a good rooting aid?

A: Yes, cinnamon is a brilliant rooting aid. Cinnamon does help plants form roots, but the most impressive thing about using cinnamon as a rooting aid is that it also aids the production of new leaves. New, strong leaves and offsets are often more desired by plant growers than excessively large roots.

Q: Do natural rooting hormones work?

A: Yes, cinnamon and honey are natural rooting aids that work rather well. Natural solutions will be more effective on some plants than others, so it really is trial and error. It certainly is worth trying a natural rooting hormone before moving onto chemical solutions first.

Q: Is using a rooting hormone dangerous?

A: Natural rooting hormones are harmless, but chemical rooting aids may be bad for other plants and animals sharing the soil. If you need to use a rooting aid, try to repot the plant into separate containers so that the chemicals aren’t transferred to plants that don’t need them.

Q: When should I use rooting hormones for my plants?

A: You should use a rooting hormone immediately after removing an offset or clipping. This needs to be done before you place the clipping into the new soil.

Q: Is honey a rooting hormone?

A: Honey is a natural antiseptic that also has anti-fungal properties. Using one tablespoon of honey mixed with two cups of boiling water will help the roots and other plant areas grow.

Q: Is saliva a good rooting hormone?

A: Yes, strangely enough, saliva is a brilliant rooting hormone! That doesn’t mean that you should use it every time to propagate your plant cuttings, but if you are curious and want to try a free way of getting the cuttings to form strong roots, you can use saliva.

Q: Do you need to add water to rooting hormones?

A: Artificial rooting hormones are often sold in powder form. Not all of them need to be mixed with water to work. Natural rooting aids, on the other hand, are often mixed with boiling water to help disperse the solution through the soil.

What rooting hormones do you usually use? We would love to hear about your experiences using rooting aids and what has and hasn’t worked for you in the past. Any tips, tricks, and methods are always welcome; drop them in the comments section below!

Delta

Thank you for this. I was going to try the honey method because I haven't got any rooting powder. Instead I'll just take cuttings and use nothing and let nature take its course.

m kocsis

i find this very interesting